Frontiers in Psychology

Activity-based mindfulness: large-scale assessment of an online program on perceived stress and mindfulness

Eliane Timm (1), Yobina Melanie Ko (1), Theodor Hundhammer (2), Ilana Berlowitz (1†) und Ursula Wolf (1†), 2024.

Front. Psychol. 15:1469316. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1469316

(1)Institute of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, (2) Eurythmy4you, Nidau, Switzerland, (†)These authors share last authorship

PUBLISHED 15 October 2024 at Front. Psychol. 18:1472562. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2024.1472562

SUMMARY OF THE RESEARCH ARTICLE

By Theodor Hundhammer, Eurythmy4you, 2024

Activity-based mindfulness: large-scale assessment of an online program on perceived stress and mindfulness

👉 Deutsche Zusammenfassung, German Summary

Abstract

Background: In recent decades, mindfulness has become a central concept in mental health. While current mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are often rooted in Asian contemplative traditions, similar practices are also found in integrative medicine systems such as anthroposophic medicine (AM).

Intervention: The Activity-Based Stress Release (ABSR) program incorporates AM as part of an 8-week online intervention, combining mindfulness exercises, behavioural self-observation, and mindful movement. This approach offers an alternative way to cultivate mindfulness, providing diverse methods to address individual differences, clinical demands, or limitations in performing certain practices.

Objective: This study used an observational repeated-measures design to evaluate the feasibility of a large-scale online implementation of the ABSR program, focusing on perceived stress and mindfulness.

Method: Participants enrolled in 37 iterations of the ABSR program. They completed four online surveys using validated stress and mindfulness scales at the beginning, middle, end, and follow-up stages of the intervention.

Results: Of the 830 participants, 53.5% completed at least two surveys, and 22.4% filled in all four surveys . As expected, mindfulness scores increased significantly, while stress scores decreased throughout the intervention. The frequency and duration of self-practice also influenced these outcomes.

Conclusion: This study provides initial indication that the online ABSR program can reduce stress and enhance mindfulness, similar to other MBIs. The findings suggest that this AM-based intervention is adaptable to an online format and offers a novel approach to existing MBIs, addressing the need for diverse methods to suit individual predispositions and clinical requirements.

Outlook: Due to the single-arm design, further controlled studies are needed to confirm these results and to identify which individuals or clinical conditions may benefit most from this method.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This study was conducted by the Institute of Complementary and Integrative Medicine IKIM in collaboration with Eurythmy4you, an accredited health provider specializing in the ABSR model.

To evaluate the online delivery of ABSR, a longitudinal repeated-measures design was used, with four assessment points to track changes in stress (primary outcome) and mindfulness (secondary outcome).

Participation was fee-based, though rates were kept minimal, with subsidized spaces for those in financial need.

The online study was promoted on the healthcare provider's website, in health magazines, newsletters, clinics offering AM services, medical practices, and on social media.

Intervention

The intervention was an eight-week online ABSR program designed to reduce stress through mindfulness practices drawn from AM. It consisted of 9 weekly 90-minute live online sessions (13.5 hours total) led by a trained ABSR facilitator, with varying amounts of self-practice over 8 weeks.

Facilitators had completed comprehensive ABSR certification, which included personal experience with the program, training lectures, a teaching practicum, and a final assessment involving a written report and presentation.

The intervention was delivered across 37 groups of various sizes and languages (English, German, Russian, Ukrainian, Slovenian, Dutch, Finnish, Chinese, and Spanish).

Each session introduced a new theme (8 modules in total) and the corresponding exercises. Participants were encouraged to practice the exercises daily for at least 15 minutes. In the following session, they could share their experiences and ask questions. Audiovisual materials and a forum were available online, and recordings of missed sessions could be accessed via the web portal.

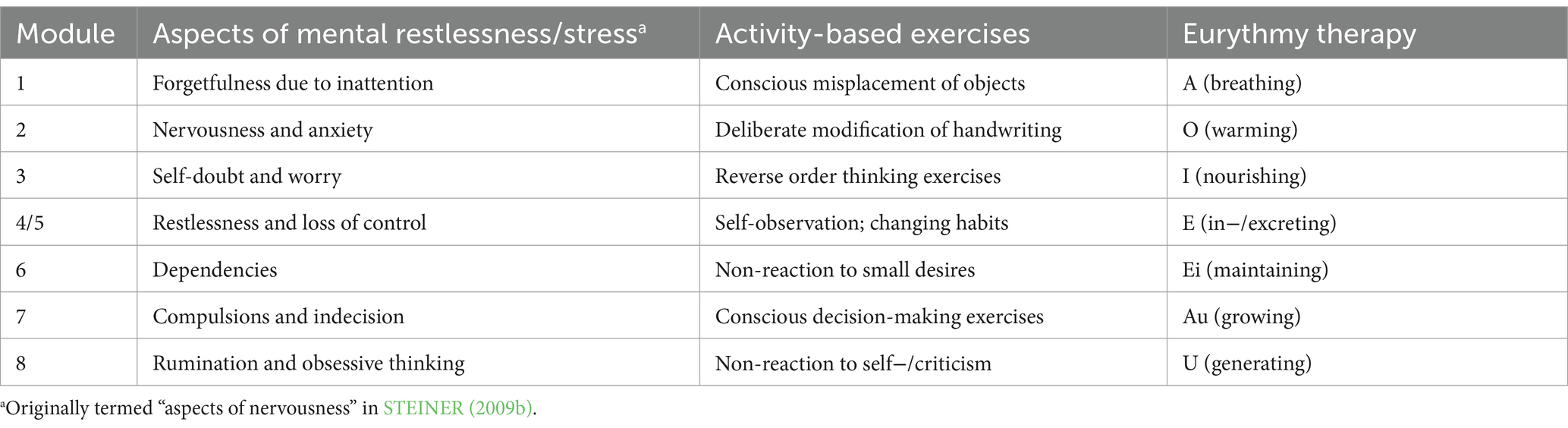

Table 1 outlines the exercises for each module, which were divided into mindful movement exercises (Eurythmy Therapy) and activity-based exercises. The latter required active performance of tasks involving physical or mental effort, despite being performed with a contemplative attitude.

Table 1. ABSR modules, themes, and mindfulness exercises.

Survey

The survey was available in six languages (English, German, Chinese, Spanish, Russian, and Ukrainian). In addition to anonymized demographic information, it included the following measures:

- Stress: The 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) measured stress levels over the past month, with higher scores indicating more stress.

- Mindfulness: The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) assessed mindfulness, with higher scores reflecting greater mindfulness.

- Self-practice and participation: Participants reported how often they practiced the exercises between sessions (days per week) and the daily time spent on them.

Surveys were conducted online at four points: upon registration (up to 3 days before the start of the program; t0), 4 weeks later (t1), at program completion (t2), and 8 weeks after that (t3). Data collection began in September 2023 and concluded in March 2024.

Data Analysis

Participants who agreed to take part and completed at least one survey were included, except for those under 18 or those who participated in more than one cycle of the program.

For analysis, Linear Mixed-Effect Models (LMM) were used as this method handles variations in the target variable over time and produces unbiased estimates even with substantial missing data, a common challenge in online longitudinal studies.

To examine, whether the frequency and duration of self-practice affected outcomes, one-way ANOVAs were conducted, testing if participants who practiced more frequently or for longer durations showed significant differences in stress and mindfulness levels compared to those with less practice.

Results

Characteristics of the Sample

- 1,155 individuals registered in the 37 implementations of the program (English-language implementations had n = 130 registrations, German: n = 259, Chinese: n = 264, Russian: n = 183, Ukrainian: n = 200, Spanish: n = 19, Finnish: n = 33, Dutch: n = 17, and Slovenian: n = 50)

- 830 agreed to participate in the study and filled in the minimally required first survey, as per inclusion criteria (full sample, N = 830).

- 444 (53.5%) filled in at least two surveys

- 186 (22.4%) filled in all four surveys.

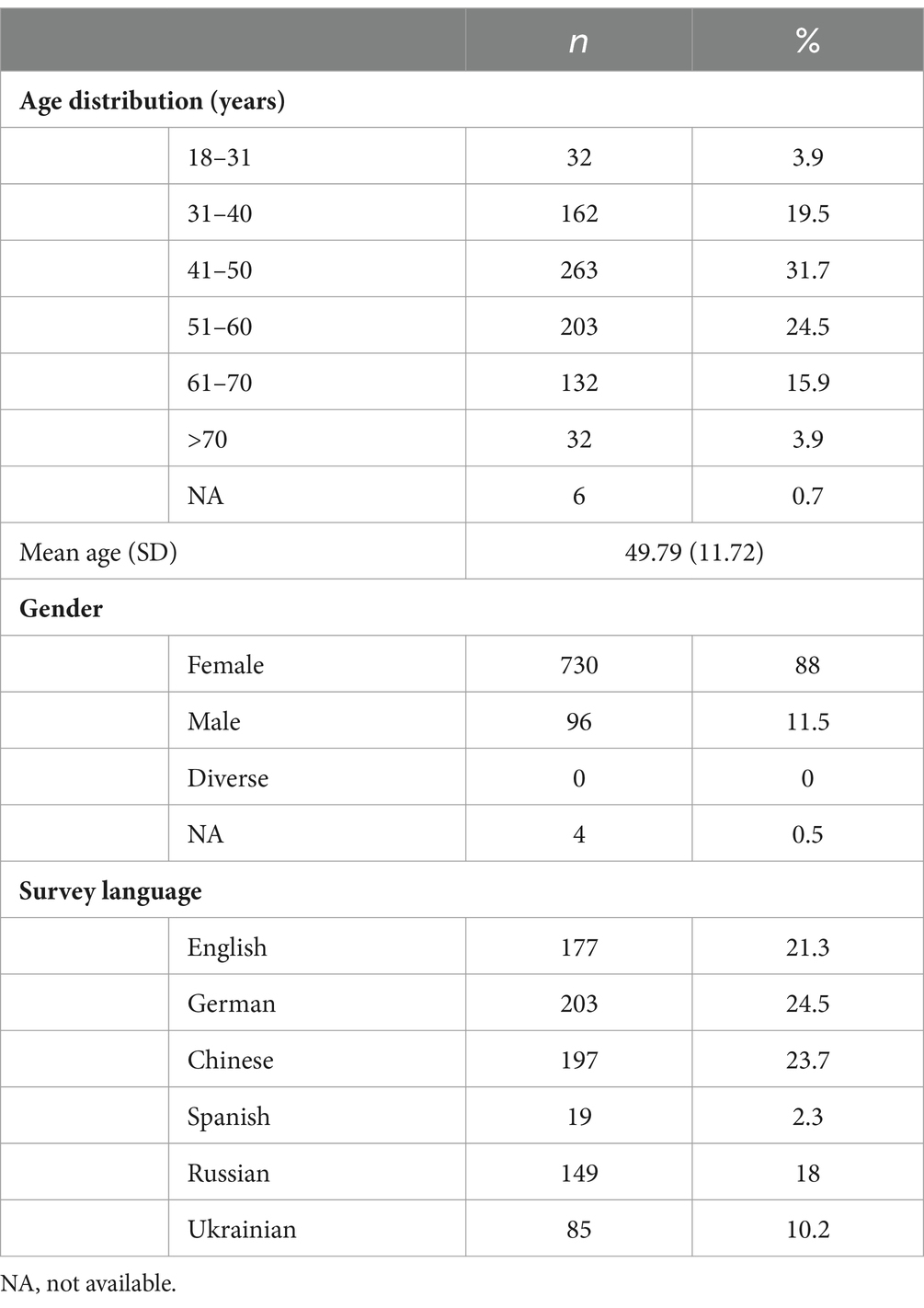

Table 2 shows the full sample’s demographic characteristics and language in which the surveys were filled in. The majority of participants were middle aged, female, and of a European context.

Table 2. Sample characteristics

Baseline

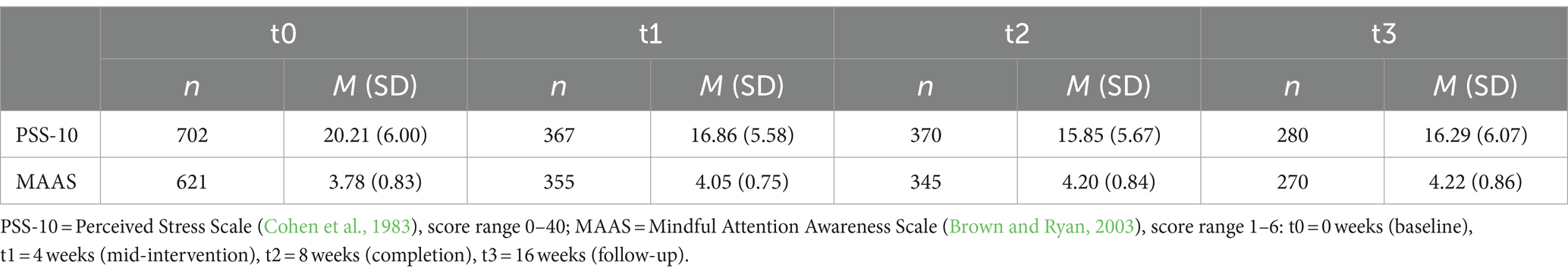

Table 3 presents the sample's stress and mindfulness levels from time point t0 to t3. At t0 (baseline), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) indicated moderate stress, higher than typical levels for healthy adults, while the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) score was slightly below average compared to general population norms.

Table 3. Self-reported stress and mindfulness per assessment time

Perceived Stress

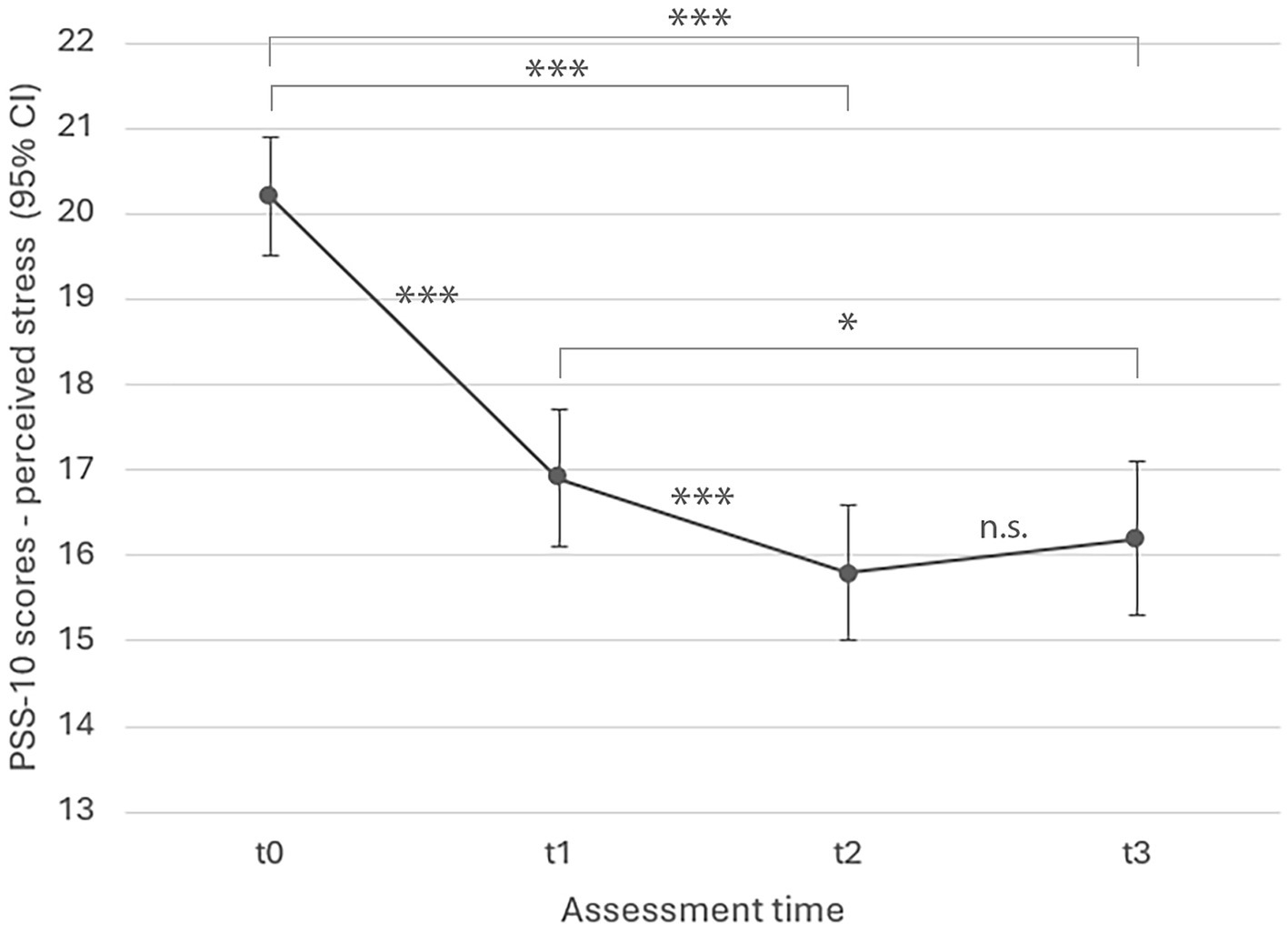

Changes in self-reported stress over the course of the study, controlled for age, sex, and survey language, can be found in Figure 2. Perceived Stress Scores PSS 10 decreased continuously from t0 to t2 and showed a non-significant small increase again at follow up. All estimates (t1, t2, t3) were significant relative to t0 at p < 0.001.The large F-value, very low p-value, and considerable effect size all support the conclusion that the intervention was effective in decreasing stress among the participants.

Figure 2. LMM model estimated marginal means for perceived stress over time (p < 0.001).

All estimates (t1, t2, t3) were significant relative to t0 at p < 0.001; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

F(3, 902) = 123.969, p < 0.001; effect size ηp2 = 0.28.

Influence of Self Practice on Perceived Stress

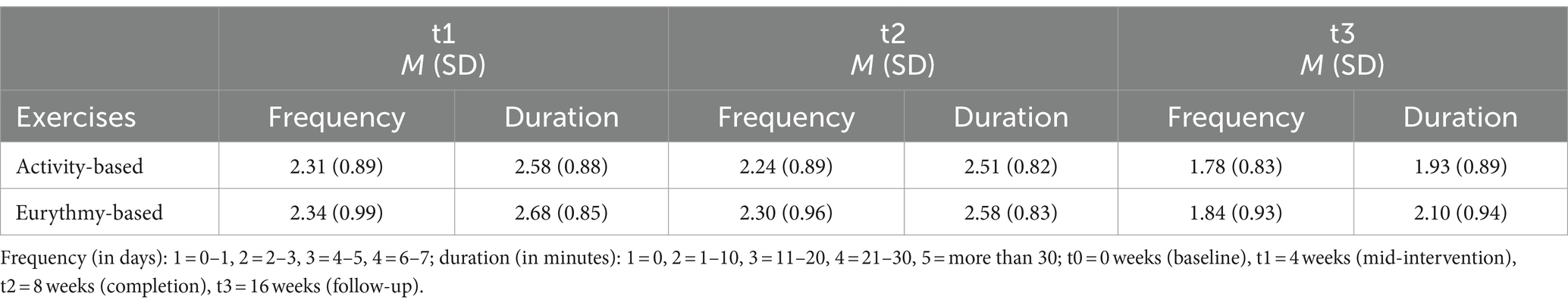

Table 4 shows the average frequency and duration of self-practice per time period.

Frequency: Participants on average practiced both types of exercises 2-3 days per week at t1 and t2, dropping to 1-2 days at t3. At t1, t2 and t3, eurythmy-based exercises were practiced slightly more frequently compared to activity-based exercises.

Duration: The average practice time was between 11-20 minutes for both exercise types at t1 and t2, decreasing slightly at t3. Eurythmy-based exercises consistently show longer durations across all time points compared to activity-based exercises.

Both exercise types, eurythmy-based exercises and activity-based exercises, show a similar frequency and duration at t1 and t2, and decrease into t3.

Table 4. Self-practice times: mean frequency and duration.

ANOVA results showed that the frequency and duration of both eurythmy-based and activity-based exercises significantly impacted perceived stress. More frequent practice of both exercise types was associated with lower stress at all time points (t1, t2, t3), while longer practice durations were linked to lower stress at t1 and t2.

For activity-based mindfulness exercises, PSS-10 scores were significantly lower with more days of practice in the weeks preceding assessments at t1 (F(3, 361) = 8.357, p < 0.001), t2 (F(3, 365) = 9.702, p < 0.001), and t3 (F(3, 275) = 4.651, p = 0.003). Longer self-practice durations also significantly reduced stress at t1 (F(4, 360) = 6.479, p < 0.001) and t2 (F(4, 364) = 3.949, p = 0.004).

For eurythmy exercises, stress scores were significantly lower with more frequent practice during the weeks before t1 (F(3, 361) = 5.567, p < 0.001), t2 (F(3, 365) = 10.18, p < 0.001), and t3 (F(3, 275) = 4.261, p = 0.006). Longer practice durations also had a significant effect at t1 (F(4, 360) = 5.297, p < 0.001) and t2 (F(4, 364) = 3.03, p = 0.018).

Mindfulness

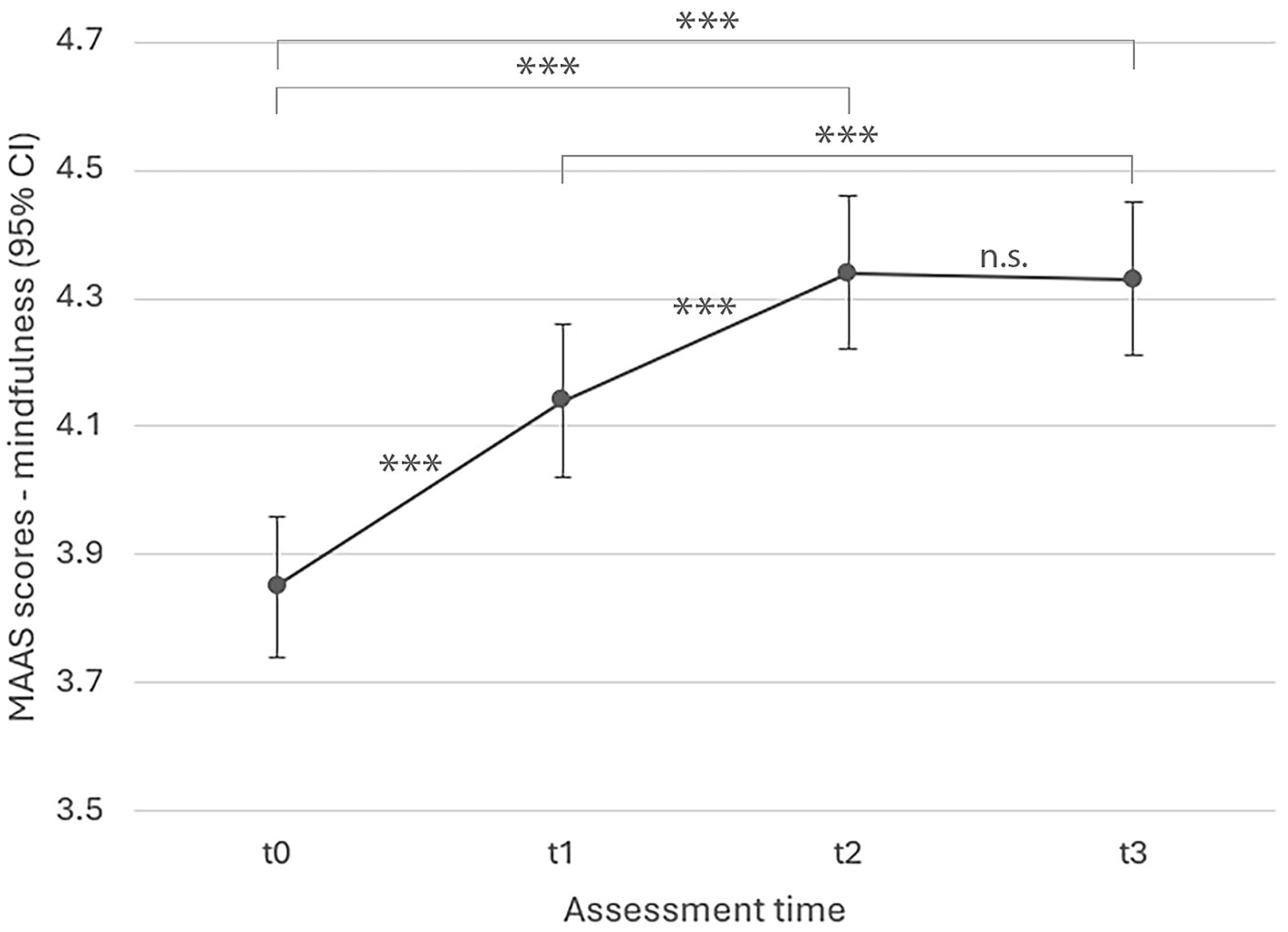

Figure 3 shows a significant increase in mindfulness throughout the intervention (F(3, 871) = 82.530, p < 0.001; effect size ηp² = 0.22), with scores consistently rising from t0 to t3. All estimates at t1, t2, and t3 were significantly higher than t0, with p < 0.001.

Figure 3. LMM model estimated marginal means for mindfulness over time (p < 0.001).

All estimates (t1, t2, t3) were significant relative to t0 at p < 0.001; ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

Discussion

The study evaluated an eight-week online MBI incorporating mindfulness practices from AM (ABSR and Eurythmy), using an observational repeated measures design with a large sample of healthy adults (N = 830).

As expected, self-reported stress significantly decreased during the intervention, with the most notable pronounced improvement occurring by week four. The lower stress level was maintained until 8 weeks after completion of the programme. This stress reduction aligns with findings from other MBIs, such as MBSR, which target stress in healthy adults.

Mindfulness, as measured by the MAAS, also significantly increased throughout the intervention, with a small, non-significant further increase at the eight-week follow-up. These results suggest that, like traditional MBIs, this intervention cultivates mindfulness, though through different methods.

Large effect sizes were found for both stress reduction and mindfulness improvement, comparable to studies using the PSS-10 and MAAS to assess MBSR (though the interpretation of LMM effect sizes across studies is still debated).

The findings showed that improvements in stress and mindfulness were sustained after eight weeks. However, a slight, non-significant rise in stress at follow-up suggests continued self-practice might help maintain benefits over the long term. Indeed, more frequent and longer self-practice was associated with greater improvements, consistent with other MBI studies linking home practice to better outcomes.

The study provides early evidence for the feasibility and benefits of an online MBI based on AM, expanding the diversity of options within the field of MBIs. The intervention’s successful adaptation to an online format also increases accessibility and affordability.

One particular limitation of the study was the single-arm observational design, which is common in early feasibility studies. Future research should use a randomized-controlled design with longer follow-up periods (e.g., 3, 6, 12, and 36 months).

Survey completion rates declined over time, which is typical of voluntary, anonymous online studies. Most dropouts occurred after the first assessment, which is a typical pattern for online interventions and has also been observed in online MBSR studies.

Future studies should consider strategies to improve completion rates, such as offering incentives or personalised reminders.

Further research is needed to explore whether this MBI is particularly beneficial for certain subgroups. Offering a variety of mindfulness practices is advantageous, but more research is required to determine which practices best suit different individuals.

Future studies should therefore assess a broader range of outcomes and clinical populations to determine for whom this AM-based mindfulness approach is most suitable. This would include assess participants' mental health and diagnoses to identify who benefits most and whether there are groups for whom the intervention may be less appropriate.

Conclusion

evidenceWhile this study provides promising early evidence for the online implementation of this novel MBI based on AM practices, these findings need confirmation through randomized-controlled studies, given the limitations of the observational single-arm design and completion rates.

Nevertheless, this research adds a unique contribution to existing MBIs, highlighting the need for diverse approaches to accommodate individual differences and clinical needs. Future research will help establish which subgroups may particularly benefit from this approach, and whether it may be less suitable for others.

October 2024

Theodor Hundhammer

Footnote: The numbers and letters represent results from statistical tests (Analysis of Variance), used to see if there are significant differences between time points or groups.

-

F(3, 902): This is the F-statistic, a value that tells us how much the groups being compared differ from each other. The numbers in parentheses indicate the degrees of freedom (the numbers that represent how much data we have). In this case, 3 represents the degrees of freedom for the differences between time points, and 902 is for the total number of participants (or data points).

-

p = 0.029: The p-value shows whether the result is statistically significant. A p-value below 0.05 (such as 0.029) means there is a significant difference, and the observed change is unlikely due to chance. If the p-value is higher than 0.05, the difference is considered not statistically significant.

- ηp2 = 0.28: ηp2 (eta-squared) is a specific measure of effect size of the strength of a phenomenon. Values range from 0 to 1. 0.01 is considered a small effect, 0.06 is considered a medium effect, 0.14 is considered a large effect and 1 indicates a perfect effect. ηp2 = 0.28 indicates that the intervention had a very large effect on stress levels, explaining 28% of the variance in stress scores. This suggests that the intervention was not only statistically significant but also practically meaningful in reducing stress.

Further Research

Publications on ABSR research can be found here: