Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience

Online eurythmy therapy for cancer-related fatigue: A prospective repeated-measures observational study exploring fatigue, stress, and mindfulness

Eliane Timm (1), Yobina Melanie Ko (1), Theodor Hundhammer (2), Ilana Berlowitz (1†) and Ursula Wolf (1†)

(1)Institute of Complementary and Integrative Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland, (2) Eurythmy4you, Nidau, Switzerland, (†)These authors share last authorship

PUBLISHED 19 September 2024 at Front. Integr. Neurosci. 18:1472562. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2024.1472562

SUMMARY OF THE RESEARCH ARTICLE

By Theodor Hundhammer, Eurythmy4you, 2024

👉 Deutsche Zusammenfassung / German Summary

Introduction

Cancer is a debilitating disease with an often chronic course. One of the most taxing and prevalent sequelae in this context is cancer-related fatigue (CRF) resulting from the disease and/or associated treatments. Over the last years mindfulness-based interventions such as eurythmy therapy, a mindful-movement therapy from anthroposophic medicine, have emerged as promising adjunct therapies in oncology.

In a prospective study, the Institute of Complementary and Integrative Medicine IKIM at the University of Bern investigated an online implementation of eurythmy therapy for cancer and cancer-related fatigue in a single-arm repeated-measures design based on two consecutive studies. Both online interventions were designed and implemented by Eurythmy4you.

Study 1: Online Eurythmy Therapy for Cancer Patients involved an initial assessment conducted before, during, after, and at follow-up of a 6-week online eurythmy therapy-based program in a mixed sample of N = 165 adults, both with and without a cancer diagnosis. The intervention utilised a specific set of eurythmy exercises commonly used with cancer patients, without additional interventions.

Study 2: Online Eurythmy Therapy and ABSR for Patients with Cancer-Related Fatigue followed a similar design, with an adapted 8-week online program in a sample of N = 125 adults diagnosed with cancer. The intervention combined eurythmy therapy with practical everyday exercises, using the Activity-Based Stress Release (ABSR) program from Eurythmy4you, specially adapted for cancer-related fatigue.

Outcomes were assessed using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue Scale (FACIT-F), the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) and the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) in Study 1 and 2, and additionally the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) in Study 1. We additionally performed an exploratory analysis regarding practice frequency and duration.

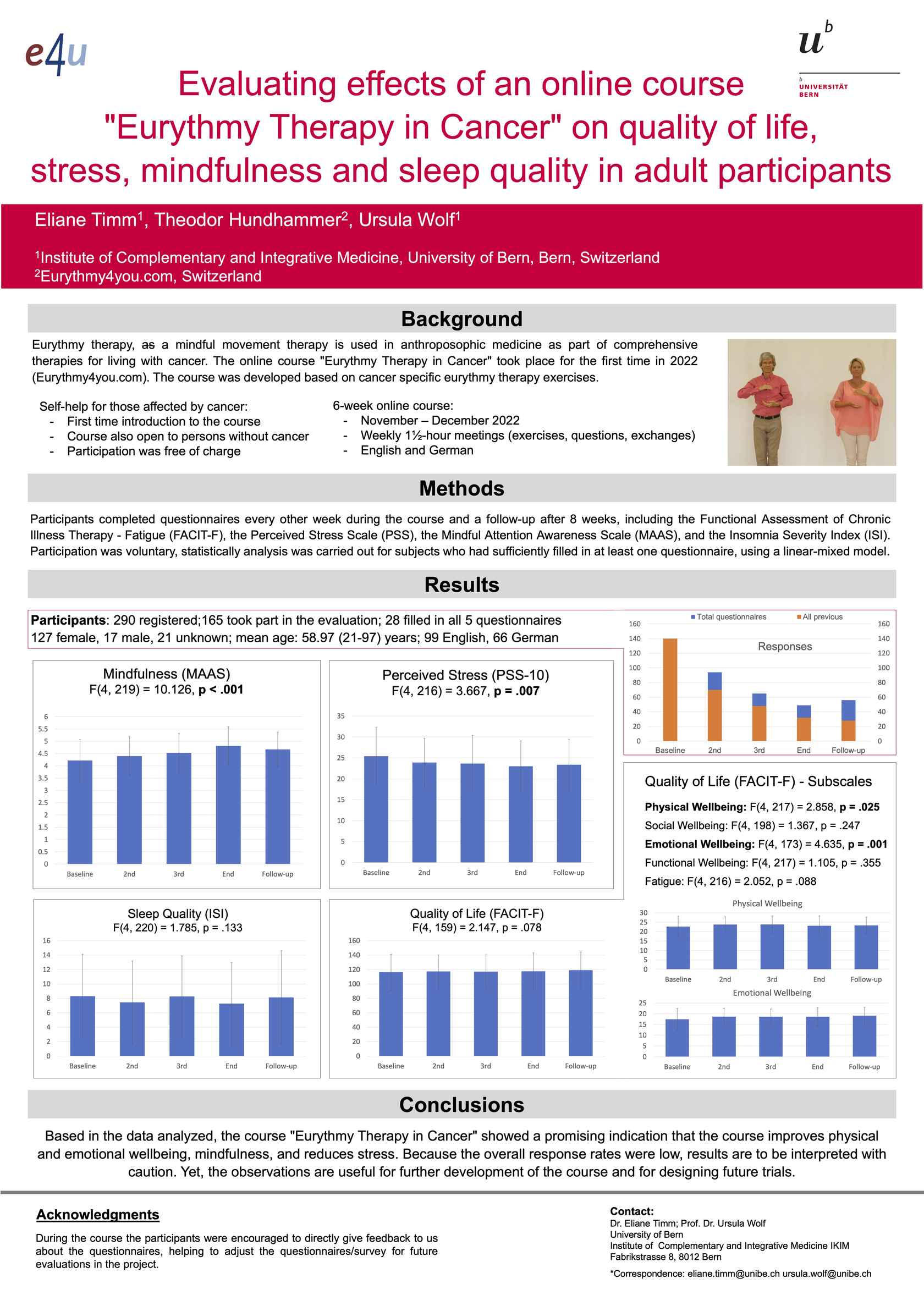

Study 1 (Eurythmy): Significant Changes in Mindfulness, Well-being and Perceived Stress

Study 1 was conducted from November 2022 until February 2023 with a mixed sample of N = 165 adults, both with and without a cancer diagnosis. The study was focusing on fatigue, sleep quality, mindfulness, quality of life indicators, and perceived stress as outcomes.

All participants were asked to complete a baseline survey at the start of the intervention (t1), followed by assessments at 2 weeks (t2), 4 weeks (t3), and 6 weeks (t4, marking the end of the intervention), as well as a follow-up at 14 weeks (t5), 8 weeks post-completion.

Key Findings

While the study found significant improvements in participants' emotional and physical well-being, as well as reductions in perceived stress and increases in mindfulness. The study did not show notable changes in levels of fatigue, sleep quality, or social and functional well-being.

For the explanation of the numbers and letters see footnote below

-

Physical Well-Being (PWB): The study found a significant improvement in physical well-being as measured by the FACIT-F scale (F(4, 197) = 2.764, p = 0.029). Significant improvements were seen at time point t2 (p < 0.05) and t3 (p < 0.01) compared to the beginning of the intervention (t1).

-

Emotional Well-Being (EWB): Emotional well-being showed even stronger improvements (F(4, 158) = 5.181, p < 0.001). Compared to the start (t1), there was significant improvement at all time points (t2 (p < 0.01), t3 (p < 0.05), t4 (p < 0.001), t5 (p < 0.001)).

-

Fatigue: Although fatigue levels improved, the change was not statistically significant (F(4, 198) = 1.948, p = 0.104).

-

Social and Functional Well-Being: Changes in social (F(4, 180) = 1.831, p = 0.125) and functional well-being (F(4, 199) = 1.227, p = 0.301) were not significant, and the overall FACIT-F score did not show a significant change (F(4, 144) = 2.362, p = 0.056).

-

Stress Reduction: There was a significant reduction in perceived stress, as measured by the PSS-10 scale (F(4, 198) = 4.110, p = 0.003). Apart from time point t2 (not significant), all other time points showed significant reductions compared to the start (t1, p < 0.01).

-

Mindfulness: Mindfulness scores, as measured by the MAAS, increased significantly during the intervention (F(4, 200) = 12.467, p < 0.001). Except for t2, all time points showed significant improvements compared to the start (t1), (t3 (p < 0.01), t4 (p < 0.001), t5 (p < 0.001)).

-

Sleep Quality: Sleep quality, as measured by the ISI, did not change significantly during the intervention (F(4, 201) = 1.724, p = 0.146).

Discussion

Fatigue: One possible reason for the lack of change in fatigue is that participants did not start the study with very high levels of fatigue. Although they had slightly more fatigue than the average healthy adult, their levels were still a bit lower than those typically reported by cancer patients. The relatively small proportion of cancer patients in the sample does not allow conclusions regarding Cancer related Fatigue, a limitation of Study 1 which we subsequently addressed in Study 2.

Stress level: The study looked at the participants' stress levels and sleep quality compared to the general population and specific cancer groups. While their stress levels were higher than the general public, they were lower than what’s often seen in breast cancer patients. Sleep quality, on the other hand, was similar to what’s typically found in people with cancer.

Practice intensity: An interesting finding was the role of participants’ own practice of Eurythmy therapy-based exercises outside of the guided sessions. In many cases, those who practiced more frequently or for longer periods seemed to experience better outcomes, such as improved well-being. However, this was not always the case and in some cases there was a correlation between exercise times of over 30 minutes per day and reduced sleep quality and functionality.

Conclusion: Although the small number of cancer patients in the study make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions, the results suggested that a eurythmy therapy-based program has potential, particularly in reducing stress and enhancing mindfulness, but more research is needed to better understand how it can specifically help with fatigue, sleep, and overall well-being in cancer patients.

These early results informed the design of the follow-up study 2.

Study 2 (ABSR): Significant Reduction in Cancer-Related Fatigue

Study 2 was conducted from September 2023 to February 2024 with a sample of 125 adults diagnosed with cancer within the past 5 years. The primary focus was on cancer-related fatigue (CRF), with stress and mindfulness as secondary outcomes. The 5-year window was chosen based on evidence that CRF may persist for up to five years or more after treatment (Bower, 2014).

To reduce participant burden, the survey was shortened by limiting the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale (FACIT-F) to the fatigue subscale, dropping the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and reducing the number of assessments from five to four. Participants completed a baseline survey at the start of the intervention (t1), followed by assessments at 4 weeks (t2), 8 weeks (t3, marking the end of the intervention), and a follow-up at 16 weeks (t4). Self-practice frequency and duration were also monitored.

Like Study 1, the intervention consisted of weekly online group sessions. The overall duration was extended to 8 weeks, and the intervention included as well Eurythmy therapy exercises and practical exercises from Eurythm4you's Activity-based Stress Reduction ABSR program (Haas, 2017).

Participants' initial Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Fatigue Subscale (FACIT-F) scores indicated clinically significant fatigue levels, well below the cut-off of 36 (Alexander et al., 2009) and reference values from a large sample of cancer patients (Butt et al., 2010). Baseline Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) scores showed moderate stress levels, similar to those in other cancer patients (Soria-Reyes et al., 2023), while Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) scores were slightly below general population norms (Brown and Kasser, 2005).

Under the assumption, that eurythmy therapy exercises in combination with additional ABSR exercises will successfully address cancer-related fatigue (CRF), participants were encouraged to practice daily for at least 15 minutes, using video demonstrations and a group forum for support.

Key findings

Study 2 found significant improvements in cancer-related fatigue (CRF), stress, and mindfulness in cancer patients diagnosed with cancer within the past 5 years.

-

Cancer-Related Fatigue: Fatigue levels showed a significant reduction over the course of the intervention (F(3, 119) = 23.618, p < 0.001), as shown in Figure 4A.

-

Perceived Stress: Stress levels also significantly decreased (F(3, 129) = 22.414, p < 0.001), as shown in Figure 4B.

-

Mindfulness: MAAS scores significantly increased over time (F(3, 128) = 24.323, p < 0.001), as depicted in Figure 4C.

For all three outcomes, estimates at t2, t3, and t4 were significantly different from t1 (p < 0.001).

Note on Figure 4A: A higher value on the scale means less fatigue.

Note on Figure 4A: A higher value on the scale means less fatigue.

Observations on Self-Practice Frequency and Duration

Stress level: The frequency of self-practice had a significant impact on stress levels. At time point t3, practising 4-5 days per week was associated with lower stress compared to practising 0-1 days (F(3, 42) = 4.248, p = 0.010). However, at time point t4, practising 4-5 days per week was linked to higher stress compared to practising 2-3 days (F(3, 36) = 2.925, p = 0.047).

Mindfulness: Similarly, mindfulness scores at time point t3 improved with 4-5 days of practice compared to 2-3 days (F(3, 41) = 3.951, p = 0.015). However, longer practice durations—more than 30 minutes—were associated with increased fatigue at time point t2 (F(4, 45), p = 0.037), compared to no practice at all.

Discussion

Limitations: Due to the voluntary nature of participation, we cannot rule out sampling bias, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, response and survey completion rates were relatively low at each assessment point — a common challenge in online, voluntary, and non-compensated studies. High dropout rates, also typical in online research, combined with the lack of a control group and randomization, further limit the interpretation of the results, calling for cautious conclusions.

Conclusion: Despite these limitations, Study 2 demonstrated significant improvements in cancer-related fatigue (CRF), stress, and mindfulness through the online intervention involving Eurythmy Therapy exercises and ABSR programs. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating controlled designs, further investigating the timing and frequency of practice, and analysing subgroups more systematically.

General Discussion

Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is a prevalent and challenging condition for many cancer patients and survivors. This study explored the potential of Eurythmy Therapy as an online intervention for CRF through two exploratory trials. Our findings suggest that online Eurythmy Therapy may help reduce CRF, improve mindfulness, and alleviate stress, marking a promising approach for addressing the needs of this population.

Despite these encouraging results, the study's lack of a control group and randomization, and relatively low response rates require caution in interpreting the findings. The voluntary nature of participation introduces the possibility of sampling bias. Future studies should try to reduce dropout and incorporate controlled designs to confirm these initial outcomes and better understand how practice frequency and duration impact therapeutic benefits.

The online format of Eurythmy Therapy presents significant advantages in terms of accessibility and scalability, particularly for individuals who are unable to leave home due to cancer treatment side effects. The group-based, adaptable nature of the exercises could make Eurythmy Therapy an affordable and easily accessible therapy option for those in need of CRF support.

In conclusion, while this study provides a promising foundation for the use of online Eurythmy Therapy to manage Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) and associated symptoms, further research is needed. Future work should aim to improve study designs, reduce dropout rates, and explore the effects of different practice schedules and patient subgroups more systematically.

October 2024

Theodor Hundhammer

Founder and CEO

Footnote: The numbers and letters in e.g. F(4, 200) and p = 0.029 represent results from statistical tests (Analysis of Variance), used to see if there are significant differences between time points or groups.

-

F(4, 200): This is the F-statistic, a value that tells us how much the groups being compared differ from each other. The numbers in parentheses indicate the degrees of freedom (the numbers that represent how much data we have). In this case, 4 represents the degrees of freedom for the differences between time points, and 200 is for the total number of participants (or data points).

-

p = 0.029: The p-value shows whether the result is statistically significant. A p-value below 0.05 (such as 0.029) means there is a significant difference, and the observed change is unlikely due to chance. If the p-value is higher than 0.05, the difference is considered not statistically significant.

Day of Clinical Research Bern, 7. 12. 2023

Posters available on request: Dr. Eliane Timm, IKIM, Universität Bern

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE